Words: Richard Hudson-Miles

Rotten’s adversaries, Pink Floyd, were synonymous with the psychedelic hippy counterculture of late 60s London. Their residency at the UFO club, Fitzrovia (1966-7) was the epicentre of a hedonistic, LSD-fuelled music scene. Here, fashion and music fused with alternative lifestyles and experimental sexualities, in a potentially world changing cocktail of liberation. However, by the early 1970s, it was clear that the revolutionary promise of this movement would remain unfulfilled. The utopian hippy dream of “peace, love, and music” had, in the UK at least, faded into social unrest, political upheaval, and poverty. Interviewed in 2006, Lydon describes 70s Britain as desperately depressing – “It was completely run down, there was trash on the streets, total unemployment”. 1973 alone saw nationwide power cuts, an oil crisis, a miner’s strike, and a failing economy stripped back to a three-day working week. To compound this, the provisional IRA commenced a mainland bombing campaign in retaliation against British rule in Northern Ireland. Though the breakthrough year of punk is generally accepted to be 1976, its preconditions were laid in these grim preceding years.

In the early 1970s, John Lydon was regularly sighted around Kings Road, London, wearing a customised Pink Floyd t-shirt. Above the band name, Lydon had scrawled the words “I HATE” in marker pen. Even before he was recruited to the pioneering punk band Sex Pistols, and had adopted the now infamous nom de guerre Johnny Rotten, Lydon’s style embodied the values for which the punk scene became renowned. Namely, insolence, anger, iconoclasm, and an anarchic disregard for social authority. This rebellious attitude rang through punk fashion as well as the three-chord assault of punk music.

Emerging from this zeitgeist, punk can be understood as the dark antithesis of the hippy era. In the eyes of the punk movement, the “turn on, tune in, drop out” ethos of the hippies was apolitical, decadent, and bourgeois. Instead, punk spoke in a language of direct action. Behind the nihilism, irony, and disaffection, it had a militant working-class ethos. Anti-establishment themes were common, as were outright declarations of class war. Part of punk’s appeal was that it offered strategies of resistance to the dismal political trajectory of seventies Britain. In those times, British society offered young people joblessness and social deprivation, wrapped in an ideological veil of past imperial glories. This national hypocrisy was foregrounded during the Queen’s silver jubilee celebrations of 1977. As the country descended towards its infamous ‘Winter of Discontent’ (1978-9), the nation was asked to throw street parties to celebrate the supposed greatness of Great Britain.

Against this nationalist triumphalism, the punk movement represented what the German-American philosopher Herbert Marcuse called the ‘great refusal’. Simply put, this refers to the capacity of the socially downtrodden to shake off pessimism and fatalism and rise up in rebellion. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the rhetoric of punk’s early figureheads The Sex Pistols. Their very first single, released on November 26th 1976, literally called for ‘Anarchy in the UK’. The public backlash about its lyrical content caused the record label EMI to drop the band after only one release. Their very next single, on the then independent label Virgin, was just as controversial. Entitled ‘God Save the Queen’, this was released during the Queen’s Jubilee celebrations and explicitly sought to provoke middle England. Like a psychotic national anthem, it screamed “There’s no future and England’s dreaming”.

SEX AND SEDITIONARIES

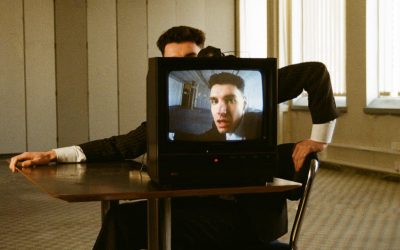

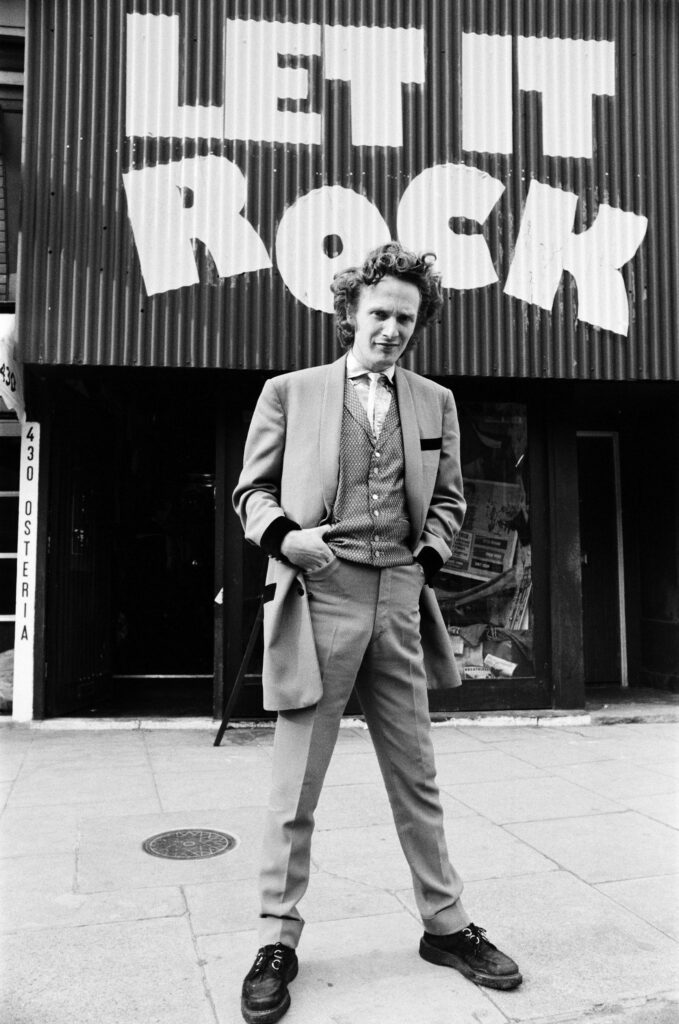

The Sex Pistols were formed in London in 1975 by the artist and impresario Malcolm McLaren. Before they had even released a single, the band played a legendary gig at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall, on June 4th 1976. This performance inspired a whole generation of alienated youths to form bands. Notably, Buzzcocks, Magazine, and Joy Division, who in turn influenced the post-punk music scene in Manchester and beyond. The Sex Pistols’ first TV appearance came in the same year, on Granada TVs cultural show So It Goes. The band deliberately drowned out their introduction by host Antony H Wilson with guitar feedback. Before the song started, Johnny Rotten screamed to the viewing public to “Get off your arrrrssseee!”. This visceral performance was matched by the band’s image. Rotten wore a customised hot-pink satin blazer, ripped at the right sleeve. Instead of an aiguillette, the ornamental gold cord worn on the shoulders of Household Cavalry officers, Rotten’s blazer was adorned with a dog chain. The drummer Paul Cook wore the aforementioned “I HATE Pink Floyd” t-shirt, and the bassist Glen Matlock wore an ‘anarchy shirt’, created by McLaren and the now world-famous fashion designer Vivienne Westwood.

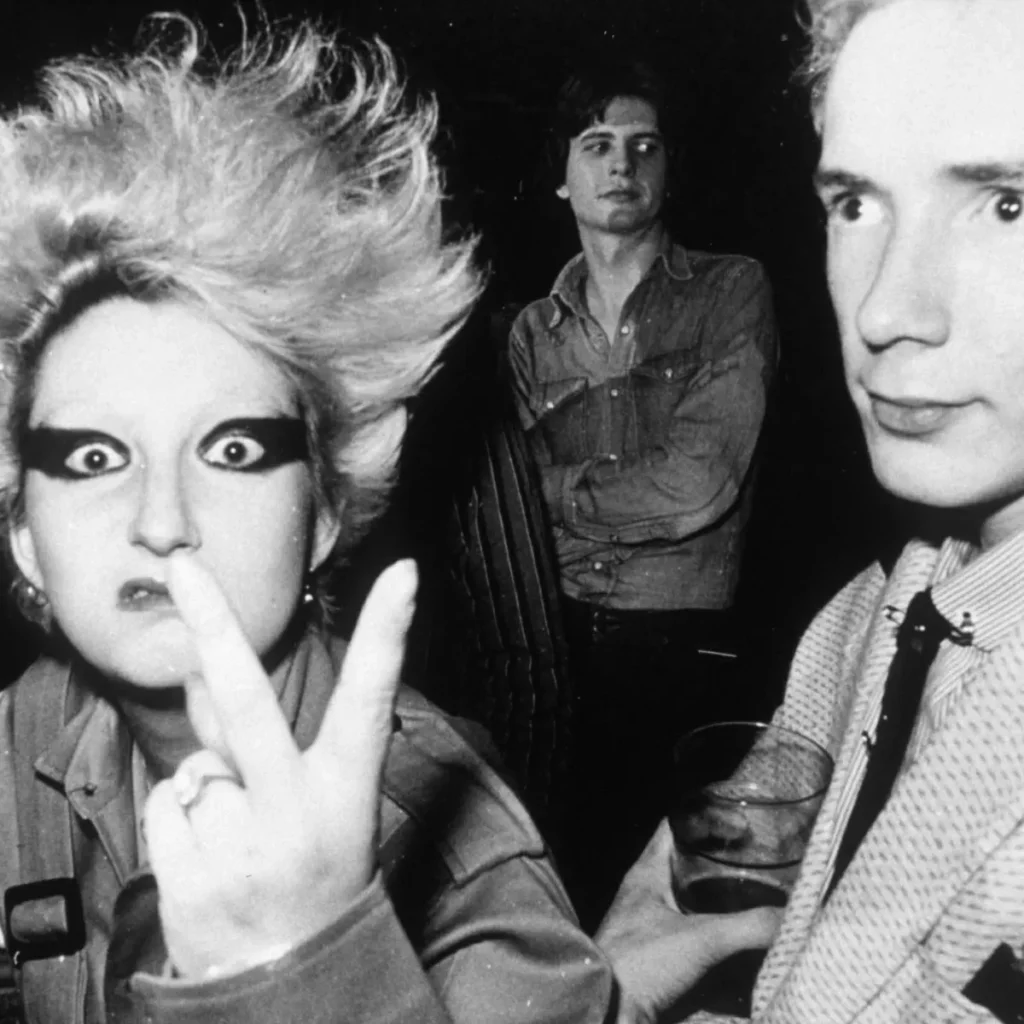

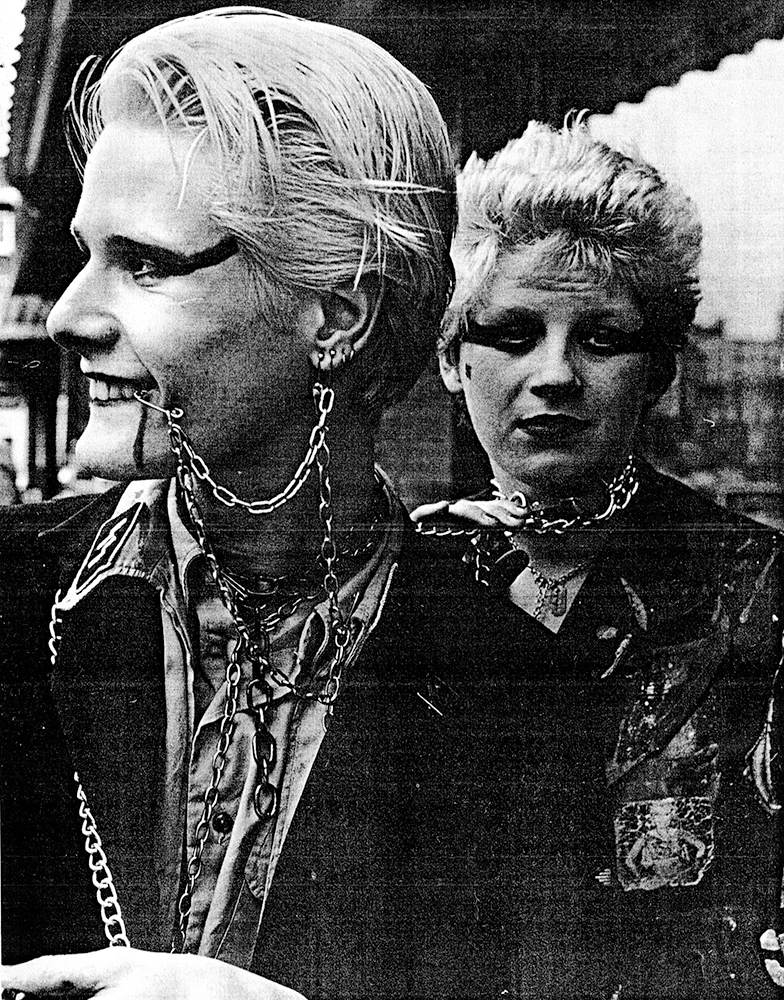

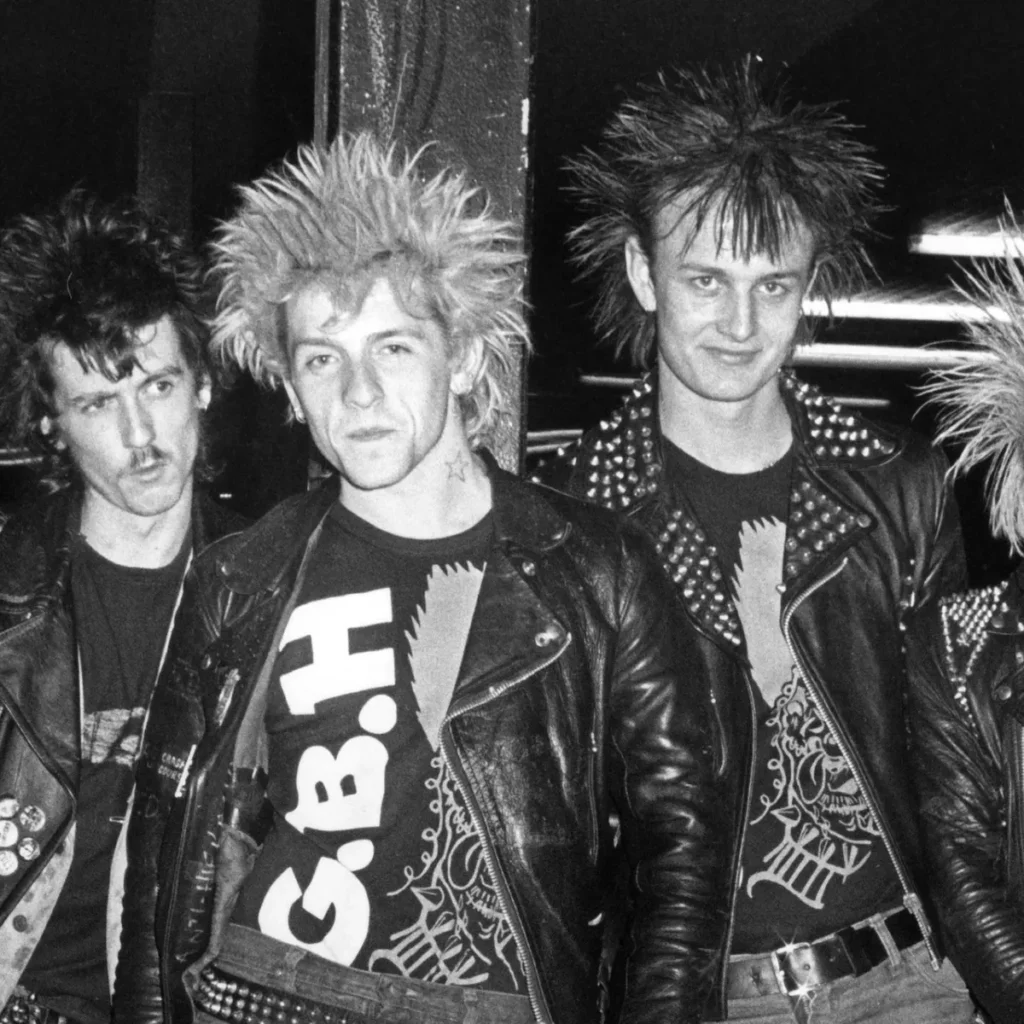

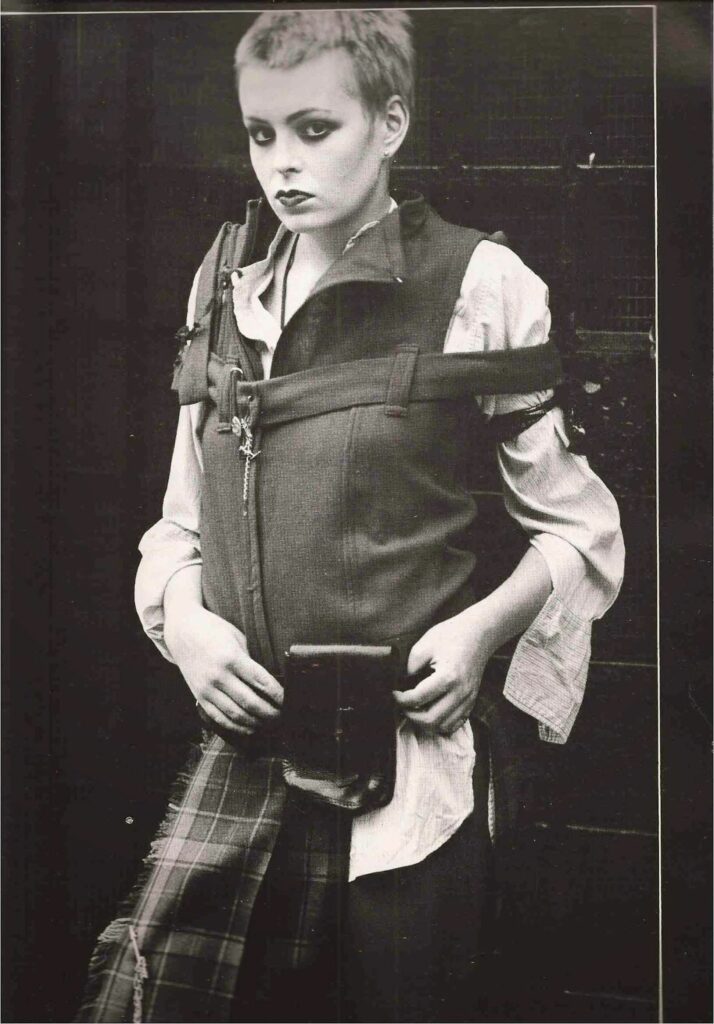

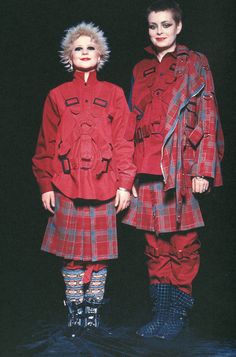

The signature Pistols style, arguably punk style generally, was created by McLaren and Westwood in their punk boutique SEX (1974-76), located at 430 King’s Rd, World’s End, Chelsea. World’s End was an old Victorian slum. In the 1970s it had turned into a rough council estate. However, this area is adjacent to some of the most expensive real estate in London. Situated on the borderlines between these two different worlds, SEX was like a punk retort to ‘royal department stores’ like Harrod’s. Its name was written in offensively large pink rubber letters above the door. The sociologist Dick Hebdige described punk style as ‘confrontation dressing’, or a form of un-fashion. Rather than chic designer labels, SEX sold modified biker jackets and trousers designed like the bondage wear of sexual fetishists. Channelling the anger and violence of the times, the clothes were often slashed with scissors or simply ripped up.

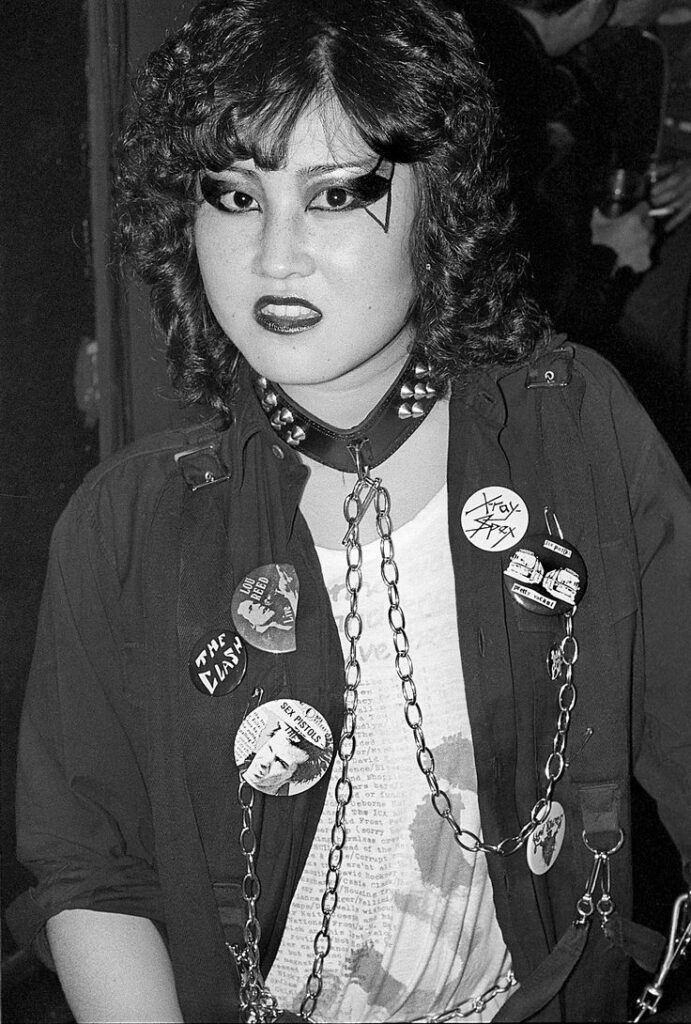

Punk style didn’t only attempt to cause offence, though it achieved this with aplomb. More importantly, it enacted a symbolic reckoning between the underground and the mainstream, between civilised society and its underbelly. For example, punk clothes were frequently covered in anti-monarchical symbols. Punks took seedy items like lavatory chains and wore them like necklaces, or turned razor blades and safety pins into jewellery. They dressed ironically in school uniforms which had been symbolically defiled. Punk style also embodied a partisan ‘us and them’ mentality. This was explicit in a t-shirt designed by Westwood and McLaren in 1974. The top of this t-shirt read “You’re Gonna Wake Up One Morning And Know What Side Of The Bed You’ve Been Lying On!”. On the left side were the names of cultural figures or institutions which were the antithesis of punk, such as Brian Ferry, Rod Stewart, the Metropolitan police, Tate & Lyle, and ‘arse lickers’ generally. The other side named those who were not necessarily punk, but embodied the punk ethos. For example, the feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, the guitarist Jimi Hendrix, the Jamaican sound system pioneer King Tubby, and pirate radio stations generally

ANARCHY IN THE UK

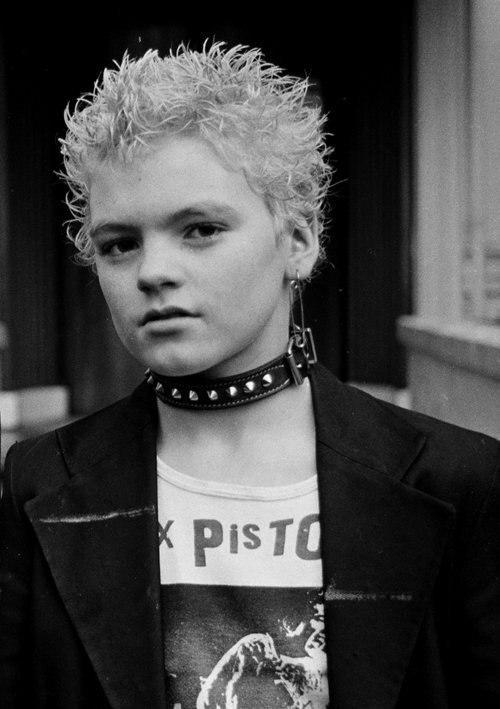

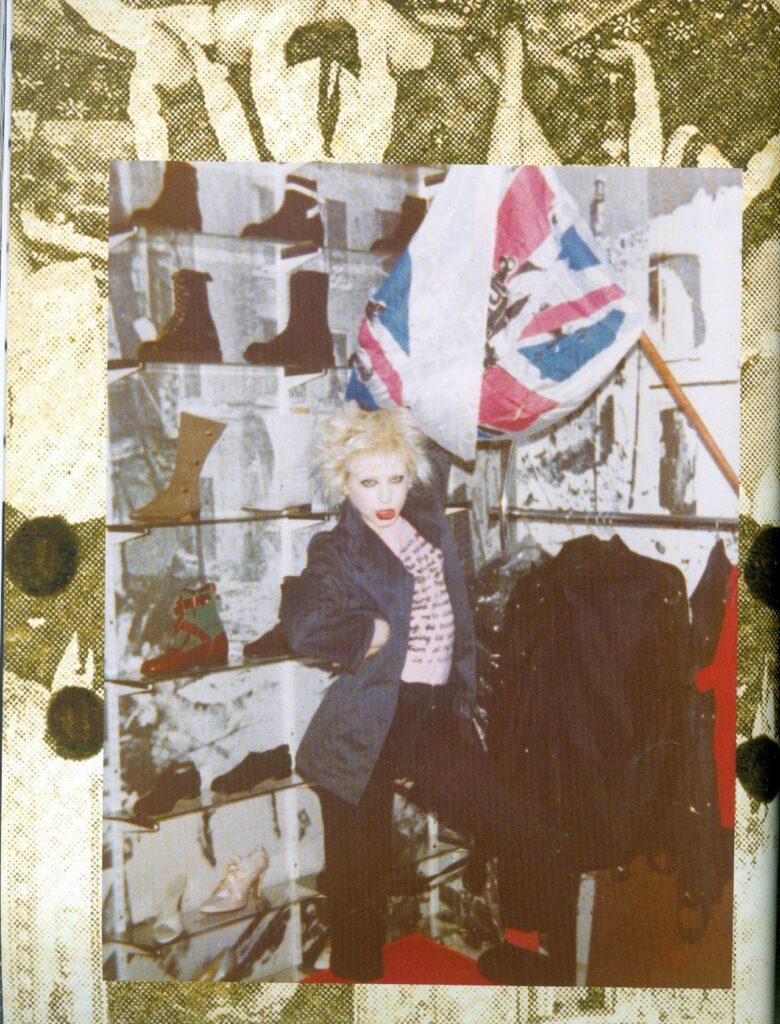

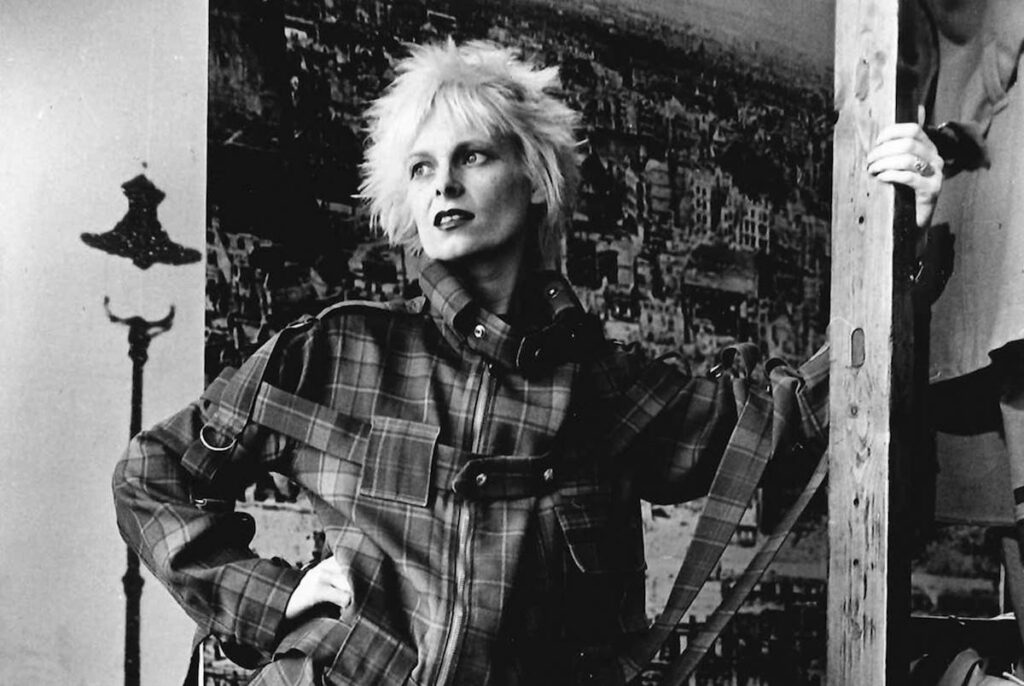

In 1976, SEX was rebranded as Seditionaries. This was also the label for the clothing made there until 1980. During this time, Seditionaries produced some of the most shocking and confrontational fashion of the twentieth century. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine many socially acceptable circumstances where one could wear these clothes, even today. A Seditionaries staple was the screen-printed and distressed white t-shirt. Often, the sleeves of these were ripped off, or the t-shirts were screen printed inside out. Invariably, the images on the front were chosen to cause maximum offence. Symbols included pornographic adaptations of Mickey Mouse and Snow White, gay cowboys, anarchy symbols, and a famous Jamie Reid design of the Queen with a safety pin pierced through her lip.

Another infamous design is the ‘Destroy’ shirt (c.1976) pictured in this article. Instead of a t-shirt, it is made from two pieces of cheap muslin cheesecloth stitched together. This fragile material would have torn and degraded with each wear, adding to the dishevelled punk aesthetic. Its sleeves are exaggeratedly long, so that it looks like the straightjacket of an escaped asylum inmate. This design was worn by Westwood herself, and Johnny Rotten, in an iconic photo by Dennis Morris (1977). However, the design’s notoriety mainly comes from the prominence of a swastika. Nazi insignia were commonplace in the punk movement, but scandalous in civilised British society. Johnny Rotten often wore a red Gestapo armband. This has been mistaken by some as a sign of a fascist tendency in punk. This is too simplistic. In punk fashion, the swastika was often juxtaposed directly with the Union Jack, in an ironic disavowal of all nationalist political symbols. More directly, it was a gesture of absolute transgression, symbolising the willingness of punk rock to push past every moral boundary imposed by polite society. For the parent class, British military heroism in WWII was unquestioned. For the punks, both Britain and Germany were warmongering fascist regimes.

Beyond the swastika itself, the composition actually suggests an anti-fascist message. ‘Destroy’ is printed over the swastika which could therefore signify ‘Destroy Nazis’. Given the prevalence of the far-right National Front on the streets of 1970s UK, this represents a brave political gesture. This gesture is complicated by the adjacent images of an inverted crucifix and the Queen’s head on a stamp. In the UK, it is criminal to deface currency or encourage treason. This design seems to achieve both feats simultaneously. If you look closely, the Queen’s head is severed at the neck, signifying the regicide of the French Revolutionary guillotine. ‘Destroy’ is also the last word of ‘Anarchy in the UK’, the lyrics of which are also printed on the shirt. Often misconstrued, anarchism is a politics of human freedom, which literally means ‘without leaders’. A popular anarchist slogan is ‘No Gods, No Masters’. In order, the images on this shirt represent politics, religion, monarchy, perhaps also money. This design therefore represents the symbolic destruction of all these fake Gods, and the liberation of a generation.

Also pictured is an equally controversial design by Westwood and McLaren (c. 1976), favoured by Sex Pistols bassist Sid Vicious. The main image of the naked black ‘footballer’ was taken from a male physique magazine called Bob Anthony’s Beefcake. McLaren bought this magazine from a gay book store in Christopher Street. The physique magazine had a unique significance within British gay culture. This specifically relates to the historic persecution of homosexuals in the UK. An archaic law called the Buggery Act (1533), which made gay sex illegal and punishable by death, had only been relaxed in 1967. Homosexuality remained the strictest of social taboos. Consequently, gay relations were forced underground, to clandestine ‘cottages’ – public toilets known only to insiders. Physique magazines were another part of this underground queer vocabulary. Publications like Health and Strength and Man’s World, ostensibly bodybuilding magazines, were sold in high street newsagents. However, nearly all the photographers who made these images were gay men. Frequent compositional references to athletes or Adonis-like Greek gods were created deliberately for the queer gaze. Same-sex encounters between the readers were arranged through the magazine’s classified adverts.

An underground variant of these magazines functioned similarly but contained much more explicit material. The Seditionaries design is taken from one such publication. These magazines were dangerous. Possession could result in arrest; trading them could lead to prosecution under the Obscenity Act (1959). Violence against the stores selling such magazines was common. This was an era of the worst homophobia, but also the moment when the gay community fought back. Inspired by the Stonewall riots (Greenwich Village, NY, 1969) against police harassment of homosexuals, the Gay Liberation Front formed in the UK in 1970. Their 1971 manifesto read ‘‘Homosexuals, who have been oppressed by physical violence and by ideological and psychological attacks at every level of social interaction, are at last becoming angry”. Fuelled by this, the very first UK Pride march occurred on 28th June 1972. Pride is now an accepted part of the mainstream cultural calendar, where even the police wear rainbow flags. In the 1970s it was a completely different story. Onlookers spat at the demonstrators, or just looked on in bewilderment. In this context, displaying a pornographic gay photograph on a t-shirt is not just offensive but political. This politics is only accentuated by the fact that the model is black and styled as a footballer. In the 1970s, black footballers were regularly subjected to monkey chants and had bananas thrown at them. This t-shirt can therefore be read as a challenge to the racism, homophobia, and toxic masculinity which still plagues British terrace culture today.

The temptation is to dismiss punk as puerile gesture politics. However, if we start thinking about it as a call to arms for the socially oppressed, we come close to understanding punk’s emancipatory legacy. Hebdige described it as guerrilla warfare waged through signs and symbols. This battle was always waged against mainstream society in the name of the marginalised. Behind the apparent nihilism, punk always encouraged affirmative action. This could be felt in DIY posters which encouraged people to learn three basic guitar chords and form bands. It was also evident in the punky-reggae parties where black and white working-class youths shared the stage. In an era of sexist cat calls and Miss World contests, the female punk band The Slits named themselves after the misogynistic jokes of patriarchy and turned guitar music into a weapon of feminism. In ‘Anarchy in the UK’, the Sex Pistols sang ‘we’re the flowers in the dustbin, we’re the poison in your human machine”. A famous young Kings Rd punk called Tuinol Barry had this tattooed across his forehead. Punk teaches a lesson of radical non-conformity which remains vital, in the age of standardised fast fashion, celebrity influencers, and generic pop music driven by major labels and reality TV