WORDS: RICHARD HUDSON-MILES. IMAGES NICHOLAS O’DONNELL

PRODUCER: ELLA KENNEALLY. STYLIST KITTY COWELL. ASSISTANT STYLISTS EMILY CORNWALL. ANASTASIA REES. MUA FRANCESCA LEACH

HAIR STYLIST SHIHORI ITO.

Outfits. KELLY OOZAGEER. MIA KITTY. JULIA LABIS

JEWELLERY: JIAWEI XU. LIYUN LU

Feminist theory, from the 1970s onwards, helped us recognise that the expected role of women in popular culture was to be the passive, sexualised objects of ‘the male gaze’. The archetypal cinematic femininity is the Bond Girl. Utterly generic and largely voiceless, her primary purpose is as a trophy for the protagonist. Her secondary purpose is to be a titillating distraction for the audience. This dynamic is even more evident in popular music. Here, female artists are expected to be seductresses first, and songwriters a distant second. Contemporary pop artists such as girli cannot be understood outside of such patriarchal discourses, nor the history of the female artists who have stood against them. In the 1970s, punk aggressively confronted patriarchal gender stereotypes. Channelling the indignation of radical feminism, bands like The Slits named themselves ironically after misogynistic locker room jokes. Prior to this, the band were called The Castrators. Rather than submissiveness, Slits songs like ‘Typical Girls’ (1979) underlined a refusal to conform to patriarchal gender roles. Instead of passive sex objects, female punks like Ari-Up, Palmolive, and Viv Albertine were what Freud called the ‘vagina dentata’. The brash individualism of the 1980s tempered the class and gender militancy of punk. Yet, post-punk artists like Debbie Harry still employed punk tactics of irony, appropriation, and refusal. Blondie were originally called Angel and the Snake. After countless instances of being cat-called “Blondie” by passing truck drivers, Harry decided to reclaim the label as a politicised band identity. The reduction of the band to a generic image of female sexuality was intended to satirise the music industry publicity machine. Ironically, the intensity of Harry’s superstar persona meant that the rest of the male band members became lost in her shadow. Debbie Harry became Blondie, and vice versa. The example of Blondie teaches us a lot about the symbolic power of the female pop icon. Namely, that the music industry’s dependence on pop star femininities to feed ‘the male gaze’ can be subverted and manipulated by savvy female artists.

More than any other female artist, Madonna has internalised these lessons. From her debut single ‘Everyday’ (1982) to the present, she has consistently demonstrated a capacity to reinvent her public persona. In the process, Madonna has shown an acute understanding of the performative aspects of media stardom. From album to album, she strategically adopted a fresh mask of femininity, discarding her old image and thus reinvigorating her career. Firstly, the NYC art scene club kid who dated Jean-Michel Basquiat. Then, the Marilyn Monroe inspired ‘Material Girl’ (1984). In the video, which was a thinly veiled critique of the music industry, various men compete to lavish the singer with gifts. Then, she mythologised her Italian Catholic background in tracks such as ‘Like a Virgin (1984) and ‘Like a Prayer’ (1989). Then, the ‘Blonde Ambition’ era where the singer weaponised her sexuality in an infamous John-Paul Gaultier corset. Subsequent reinventions included the Queer Madonna (‘Vogue’, 1990), the Pornographic Madonna (Erotica, 1992), the Evita Madonna (1996), and the Mystical Hippy Madonna (Ray of Light, 1998). More recently, the singer has moved from a maternal image to a Cristal swigging, Queen of street music. The point, which Madonna knows only too well, is that we will never get to know the real Madonna Ciccone. Self-aware, industry savvy, sex-positive, and always in control of her own image, Madonna is in many ways a feminist icon. Universities now run modules in ‘Madonna Studies’, and all contemporary female pop stars stand on her shoulders. In a 2013 article, popular music historians Tara Brabazon and Steve Redhead argued that Lady Gaga played the same game as Madonna, but had condensed her four decades of fame into five years. This is not a critique of Lady Gaga. It is simply an acknowledgement that successful female pop stars are always already a tissue of quotations from pop history. The era of social media has simply accelerated the need for novelty, and the necessity for rapid self-reinvention. Pop stars today are hyperreal bricolage. All of these intertwined histories coalesce within the short, but incredibly successful, career of girli. Since 2015, she has released over twenty high-energy electro-pop singles, alongside a debut album, ‘Odd One Out’ (2019). These tracks have gained her a large following, largely amongst the Gen Z community who embrace girli’s themes of mental health, identity politics, body dysmorphia, and unrequited love. As a self-identifying queer, pansexual, and feminist singer, she has also become an icon of the LGBTQIA+ scene. Deservedly, she headlined Prague Pride this year. Her last EP, ‘Damsel in Distress’ got over 40 million streams on Spotify alone, and girli is hoping for a similar reception for her new single, ‘I Really F**ked It Up’, available now via All Points/Believe.

Girli has described this as her most “unapologetically pop era yet”. This single certainly has the elements of lovelorn angst which have become the hall-marks of teen pop since the 1950s. However, despite her signature pink hair and visual identity, it would be a mistake to dismiss girli as lightweight. She is an educated, intelligent, and forthright artist whose lyrics leave no doubt that she is taking on the patriarchy. By choosing the name ‘girli’ she deliberately inviting a confrontation with the sexist culture which equates girliness with frailty, submissiveness, and triviality. girli has previously stated that she wanted to “reclaim the word ‘girly’ and to make pink punk again”. Like Madonna, Lady Gaga, and Blondie, she also slips in and out of the tropes of femininity with ease.

In the video for the single ‘Friday Night, Big Screen’ (2019) she adopts a Rita Hayworth persona of Hollywood Glamour. The song relates to the processes of projection and self-identification between audience and movie star. Lyrics like “livin’ it, through a TV screen / Now it’s real / It’s all happening to me / This is life in the movie” also relate to the escapism of glamming up for the weekend. However, they also subtly refer to the performative and hyperreal aspects of pop stardom.

A completely different girli was presented in the video for an earlier single, ‘Girls Get Angry Too’ (2016). Via a hyperactive jump-cut, girli switches styles rapidly, alternating between a conventionally feminine bubble-gum pink princess and a more masculine B-Girl / Run DMC Adidas streetstyle. Defying all stereotypes of girliness, she raps “Girls get naughty, boys tell ’em behave / hypermasculinity, drowning the vicinity / weakness is just another word for femininity”. Later, she warns that “girls get angry too / I’m a samurai princess, I’ll smash you / samurai prince, glue your lips in two”.

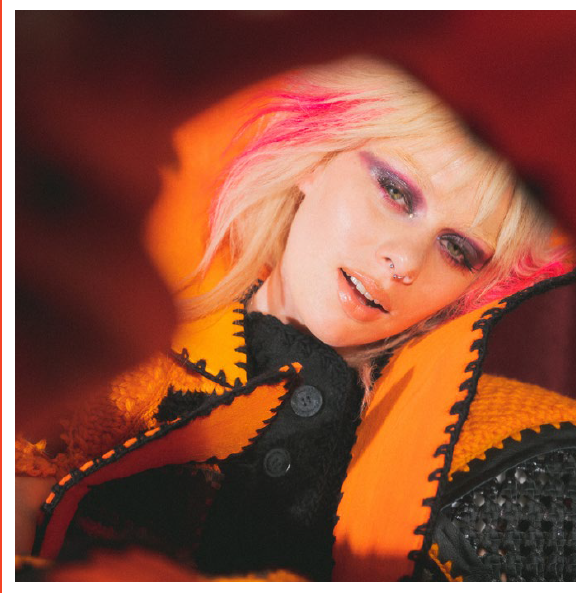

girli displayed a more vulnerable side on the recent ‘I Don’t Like Myself’ (2021). This opens with the lyrics “I’ve been looking myself up and down checking all my flaws out / I’ve been saying shit to the mirror that isn’t nice for quite a while”. Unfortunately, this critical self-scrutiny is the condition forced upon many young women in the social media age. However, girli is no passive victim. The inspirations she channels to pick herself up are Rosa Parks and Kate Moss. In different ways, both are triumphant figures of female power. In this video, she wears pink joggers, pink plaited Judy Garland / Dorothy pigtails, and a t-shirt saying ‘Toxic Masculinity Seriously Harms You And Others Around You’. The common denominator of all of this is the colour pink, which is transformed by girli into a symbol of righteous feminist anger. girli insists that “pink was always my superpower; pink is powerful”. Like the pink pussyhats worn by feminist protesters against the Donald Trump presidency, or the pink triangles displayed by LGBTQIA+ activists, girli has reclaimed pink as a weapon in the struggle. Transforming a previously oppressive label into a symbol of resistance is an incredibly powerful tactic. This might just be pop music, but here girli aligns herself with Debbie Harry’s peroxide hair, Madonna’s razor-sharp cone bra, and The Slits’ in your face gynaecology. Girli has admitted that she wants to be “a modern-day Debbie Harry”, and even has a tattoo of Harry on her arm. It is surprising, but also not, that girli has abandoned her trademark pink locks to promote the new single. In a nod to her heroine, she now sports Harry-esque peroxide hair with pink highlights. girli explains, “I wrote this song about doing destructive things to feel excitement, and absolutely hating myself for it. Writing this song made the whole project fall into place; why am I like this? Who is controlling my puppet strings when I do things I don’t want to do?”. Clearly, this new incarnation of girli has an element of catharsis, which her army of Gen Z fans will immediately empathise with. However, the new, blonder girli is also the strategic reinvention of a sassy, savvy, pop star who is pulling her own strings and always two moves ahead of stereotypes.

girli’s new single, I Really F**ked It Up is available now via AllPoints/Believe.