Words: Richard Hudson-Miles

There was a time, roughly stretching from the late 1980s to the election of Mayor Rudy Giuliani in 1994, when New York City was the most anarchic, experimental, and dangerous party city on the planet. This period gave rise to a notorious generation of hedonistic queer youth known as the Club Kids. These party animals have since become legendary for their outlandish experiments in D.I.Y. club style, their irresistible youthful charisma, their razor-sharp cheekbones and genderfluidity, their insatiable appetite for drugs and sex, and the petulant shade they threw at everyone who crossed their path. Most importantly, they are remembered for the bacchanalian parties they organised in previously unfashionable clubs like Danceteria, The Palladium, The Tunnel, and The Limelight. These club nights overlapped with the Ecstasy-driven euphoria of the early rave scene. However, they also channelled a darker range of influences, which spread from the wild cabaret shows of Weimar Germany, the grungy art scene of the East Village, the performance art of Leigh Bowery, the seedy sex shows of Times Square, and the D.I.Y. fashion found at the gritty music venue CBGB’s and the burgeoning New York City punk scene.

To understand the importance of the Club Kids, you need to know something about the context of New York City in the late 1970s, which was markedly different to the gentrified metropolis you see today. The Lower West and East Sides of Manhattan, where the Club Kids held most of their parties, were largely derelict and dangerous no-go zones, frequented by criminal gangs and drug addicts. Many of what would now be considered as the most desirable real estate on the planet laid empty, used as crack houses and stripped to the bare bones of anything which could be sold for drugs. Crack pipes littered the streets of Alphabet City, which is now a trendy, professional neighbourhood filled with cafés and craft cocktail bars. In the early 80s, many of its streets lacked even basic lighting. Many downtown districts had a dark, dangerous energy. Times Square, which is now globally recognised as a space of glitzy commerce, was then dominated by the sex industry. Every other shop was a strip club or pornographic theatre. Hookers brazenly solicited passing curb-crawlers in broad daylight. Many parts of the city were still controlled by the mafia. For many, NYC was deemed to be an unsalvageable, lost city. At the same time, NYC was a city of immense wealth and privilege, especially during the yuppie boom of the 1980s. These two sides of Manhattan frequently coalesced in the art scene of the East Village, which transformed homeless street kids like Jean-Michel Basquiat into millionaire darlings of the art world overnight. Looming large over this particular scene was Andy Warhol, who gathered together various waifs and strays from the NYC streets as his acolytes. He rebranded these as his ‘superstars’, within his ‘Factory’ system, and famously insisted that everyone and anyone is entitled to their fifteen minutes of fame. The Club Kids were quintessential Warholian figures, always seeking publicity, new opportunities to promote their brand, or to scandalise mainstream American media. Speaking on The Jane Whitney show in 1993, Waltpaper (previously Walt Cassidy) casually boasted that “we get paid to go to clubs, do drugs, run around, have fun, and look glamorous”.

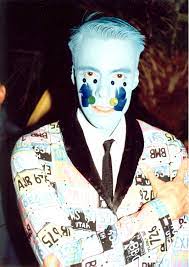

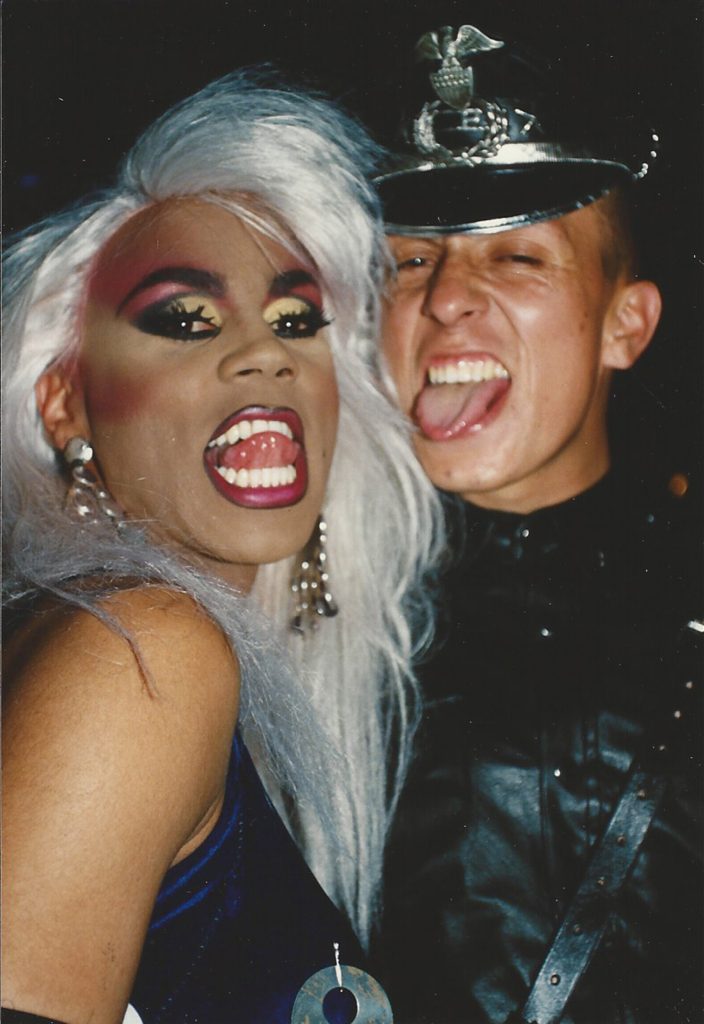

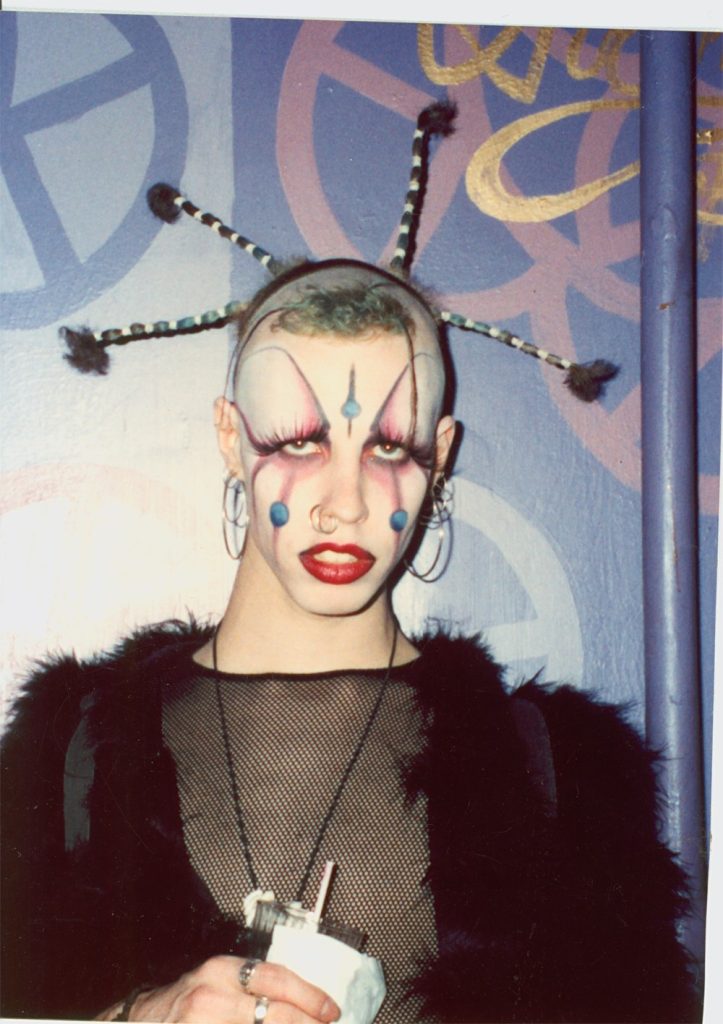

Most of the Club Kids adopted flamboyant nom de plumes, which were frequently erotic innuendos. Aside from Waltpaper, some of the more interesting of these were Jenny Talia (Jenny Dembrow), Desi Monster (Desi Santiago), Astro Erle, Richie Rich, and Kabuki Starshine, all of whom became legendary faces within the scene’s inner circle. These figures would compete to be seen at parties in the most extravagant outfits imaginable. Often, these were made from improvised household materials in true punk spirit. Jenny Talia sported an army grade shaved head, and regularly wore see through gold lurex tops with nothing underneath, and a metal spike which travelled across her mouth and through both cheeks. Desi Monster was famous for having a completely bald head, apart from four braided, fluoro locks of hair which sprouted at odd angles from his head like the stalks of strange weeds. Astro Erle’s image was so fabulous that she was paid in drinks tickets to attend the seminal Club Kids party Disco 2000. This party was run at The Limelight by Michael Alig, arguably the figurehead and architect of the entire Club Kids scene. The Limelight was an unusual club venue, constructed from the Gothic Revival shell of the abandoned Church of the Holy Communion in Chelsea. The Club Kids relentlessly exploited this religious history, turning up to raves dressed as Satanic nuns and fallen angels. Their skin-tight outfits, which often displayed far more flesh than they concealed, were accentuated by inverted crucifixes and prosthetic wings. At one party, clubgoers carried a life-size cross carrying a Jesus figure in a loincloth past placard-wielding picket-lines of scandalised religious protestors. Inside, like the last days of Sodom and Gomorrah, Go-Go dancers were lowered from the ceiling in steel cages, and people openly snorted cocaine and fornicated beside the dancefloor. Through a hole in the wall, drug dealers dispensed vodka shots laced with ketamine and psychedelic mushrooms, and a guy in a yellow chicken suit danced wildly on the stage. Club Kids’ parties were so popular that they would frequently start on Friday evening and run straight through to Monday morning. Staggeringly, Disco 2000, by far the most influential night of the Club Kids era, ran on a Wednesday night. Most promoters would struggle to half-fill a venue mid-week, but Alig’s reputation was such that the club invariably turned people away in droves, even before social media. Celebrity pop stars like Grace Jones, Madonna, Nina Hagen, even George Michael, started attending the parties in appropriately outré fashion. Before the ‘flash-mob’ had even been given a name, Alig also pioneered what he called ‘Outlaw Parties’. Here, the Club Kids took the party to the NYC streets, meeting at prearranged public spaces, in their weirdest outfits, to set up sound-systems and party until the police moved them on. Many of these flash-mob raves took place in abandoned warehouses and parking lots. One took place in a subway station, and another in a McDonald’s, to the utter bemusement of its dining customers. Clearly, the act of transformation, or transgression, was absolutely integral to the Club Kids scene. Writing about mediaeval carnivals, the Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin identified, within the bawdy crowd, a similarly revolutionary spirit which he called the ‘carnivalesque’. In the ancient festivals, authority figures were lampooned by the everyman, who cast aside their everyday identities to become new fantastical figures for the day. For Bakhtin, the carnival, with its lawless, intertwined bodies and newly reinvented subjectivities was analogous to a social revolution. The Club Kids nights also embodied this anarchic ‘carnivalesque’. In this sense, those endless NYC party nights in the early 90s were both counter cultural and political. In a recent interview, Astro Erle confirmed as much: “I am an anarchist. I don’t believe in the system, I don’t believe in eating meat, I don’t believe in paying taxes. I’ve been a vegan most of my life and the (rental) rates that they ask for and globally raising rent, it’s too much”. For the Club Kids, partying was not simply hedonism, but a total rejection of the values of mainstream society.

For many, the nights at The Tunnel and The Limelight functioned as a safe-space for all of NYC’s outcasts; a home for all the freaks and weirdos in need of one. At one point over thirty of the Club Kids lived together communally in the infamous Chelsea Hotel. Certainly, their club nights were the model of inclusivity, with goths, gays, punks, yuppies, celebrities, and street hustlers all cavorting in unison. Simultaneously, the Club Kids project was social, political, and artistic. Not only did Club Kids performatively transform themselves into otherworldly creatures, rejecting the labels and insults of mainstream society in the process, they also turned the grimy, forgotten, urban spaces they inhabited into living, breathing, works of participatory performance art. It should be emphasised that before the Club Kids made it their spiritual home, and the unlikely epicentre of NYC nightlife, The Limelight was sarcastically known as ‘The Slimelight’. Similarly, within this emancipatory subculture, a shy, mid-western, queer boy like Michael Alig could metamorphose into the beautiful, sassy, all-conquering king of clubland. The Club Kids were all self-made celebrities, many of them from the wrong side of the tracks, who weaponised their looks, attitude, and renegade style, to claim a celebrity status which, however fleeting, would not have been given to them in everyday life.